Lawrence of Arabia and dignitaries, 1921 The purpose here is not to duplicate the original image, from the Library of Congress website, but to generate a downloadable animated gif to assist viewing and presentation.The original image is titled Sir Herbert Samuel's second visit to Transjordan, etc. Sir Herbert, Col. Lawrence, Emir Abdullah.

Sir Thomas Lawrence: The Calmady Children. Metropolitan Museum. New York

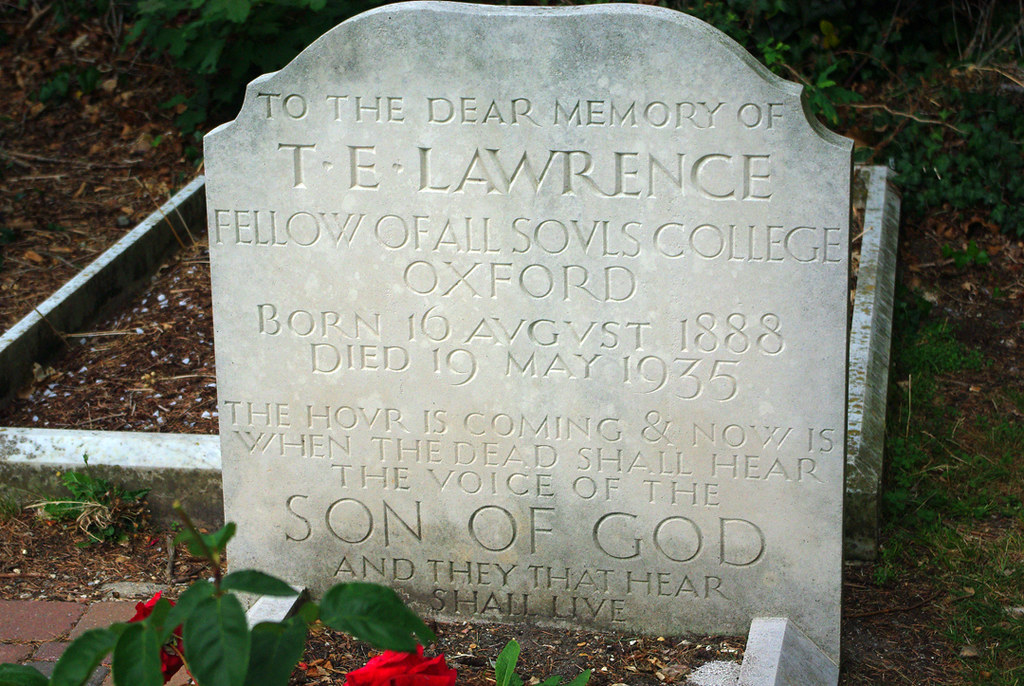

Lawrence was born illegitimate in Tremadog, Wales, in August 1888 to Sir Thomas Chapman and Sarah Junner, a governess who was herself illegitimate. Chapman had left his wife and first family in Ireland to live with Sarah Junner, and they called themselves Mr and Mrs Lawrence. In the summer of 1896 the Lawrences moved to Oxford, where in 1907–10 young Lawrence studied history at Jesus College, graduating with First Class Honours. He became a practising archaeologist in the Middle East, working at various excavations with David George Hogarth and Leonard Woolley. In 1908 he joined the OUOTC (Oxford University Officer Training Corps), undergoing a two-year training course.[6] In January 1914, before the outbreak of World War I, Lawrence was co-opted by the British Army to undertake a military survey of the Negev Desert while doing archaeological research. Lawrence's public image resulted in part from the sensationalised reportage of the revolt by an American journalist,Lowell Thomas, as well as from Lawrence's autobiographical account, Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1922). Early life

T. E. Lawrence's birthplace, Gorphwysfa, now known as Snowdon Lodge. Lawrence was born on 16 August 1888 in Tremadog, Caernarfonshire (nowGwynedd), Wales, in a house named Gorphwysfa, now known as Snowdon Lodge.[8] His Anglo-Irish father, Thomas Robert Tighe Chapman, who in 1914 inherited the title of Westmeath in Ireland as seventh Baronet, had left his wife Edith for his daughters' governess Sarah Junner. Junner's mother, Elizabeth Junner, had named as Sarah's father a "John Junner -- shipwright journeyman", though she had been living as an unmarried servant in the household of a John Lawrence, ship's carpenter, just four months earlier. The couple did not marry but were known as Mr and Mrs Lawrence.

Gwesty`r Wyddfa yn 1930.. snowdon hotel in the 1930`s

Stryd y LLan Tremadog yn 1950.. Church street Tremadog in the 1950`sThomas Chapman and Sarah Junner had five sons born out of wedlock, of whom Thomas Edward was the second eldest. From Wales the family moved to Kirkcudbright in Dumfries and Galloway, then Dinard in Brittany, then to Jersey. From 1894–96 the family lived at Langley Lodge (now demolished), set in private woods between the eastern borders of the New Forest and Southampton Water in Hampshire.

Cei llechi Porthmadog yn 1904. Slate quay in Porthmadog in 1904Mr Lawrence sailed and took the boys to watch yacht racing in the Solent off Lepe beach. By the time they left, the eight-year-old Ned (as Lawrence became known) had developed a taste for the countryside and outdoor activities. Lawrence memorial plaque atOxford Boys' High School In the summer of 1896 the Lawrences moved to 2 Polstead Road in Oxford, where, until 1921, they lived under the names of Mr and Mrs Lawrence. Lawrence attended the City of Oxford High School for Boys, where one of the four houses was later named "Lawrence" in his honour; the school closed in 1966.

Twnel Penmaenbach cyn eu agor yn 1932. Penmaenbach tunnel before it` opening in 1932

As a schoolboy, one of his favourite pastimes was to cycle to country churches and make brass rubbings. Lawrence and one of his brothers became commissioned officers in the Church Lads' Brigade at St Aldate's Church.

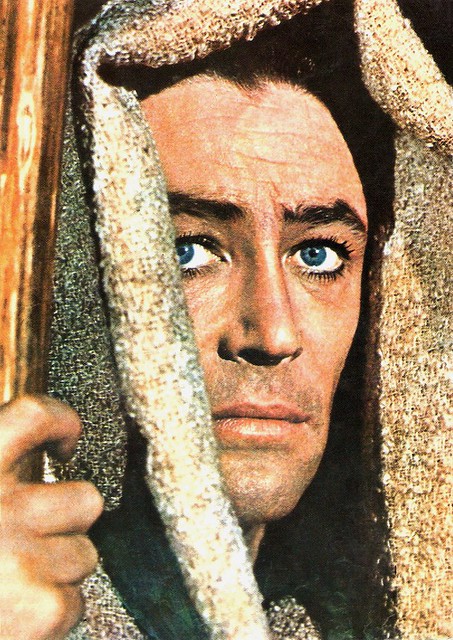

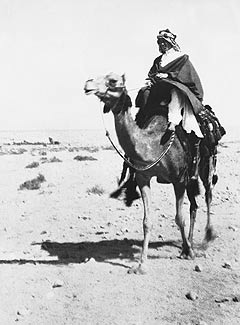

Stryd y Llan Tremadog circa 1935.. Church street Tremadog circa 1935Lawrence claimed that in about 1905, he ran away from home and served for a few weeks as a boy soldier with the Royal Garrison Artilleryat St Mawes Castle in Cornwall, from which he was bought out. No evidence of this can be found in army records.[12] Middle East archaeologyAt the age of 15 Lawrence and his schoolfriend Cyril Beeson bicycled around Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire, visited almost every village's parish church, studied their monuments and antiquities and made rubbings of their monumental brasses.[13] Lawrence and Beeson monitored building sites in Oxford and presented their finds to the Ashmolean Museum.[13] The Ashmolean's Annual Report for 1906 said that the two teenage boys "by incessant watchfulness secured everything of antiquarian value which has been found".[13] In the summers of 1906 and 1907 Lawrence and Beeson toured France by bicycle, collecting photographs, drawings and measurements of medieval castles.[13] From 1907 to 1910 Lawrence studied history at Jesus College, Oxford.[14] In the summer of 1909 Lawrence set out alone on a three-month walking tour of crusader castles inOttoman Syria, in which he travelled 1,000 mi (1,600 km) on foot. Lawrence graduated with First Class Honours after submitting a thesis entitled The influence of the Crusades on European Military Architecture—to the end of the 12th century based on his field research with Beeson in France,[13] notably in Châlus, and his solo research in the Middle East.[15] Leonard Woolley (left) and T. E. Lawrence at Carchemish, ca. 1912 On completing his degree in 1910, Lawrence commenced postgraduate research in mediaeval pottery with a Senior Demy, a form ofscholarship, at Magdalen College, Oxford, which he abandoned after he was offered the opportunity to become a practising archaeologist in the Middle East. Lawrence was a polyglot whose published work demonstrates competence in French, Ancient Greek, and Arabic. T. E. Lawrence and Leonard Woolley(right) at Carchemish, spring 1913 In December 1910 he sailed for Beirut, and on arrival went to Jbail (Byblos), where he studied Arabic. He then went to work on the excavations at Carchemish, near Jerablus in northern Syria, where he worked under D. G. Hogarth and R. Campbell Thompson of theBritish Museum. He would later state that everything that he had accomplished, he owed to Hogarth.[16] As the site lay near an important crossing on the Baghdad Railway, knowledge gathered there was of considerable importance to the military. While excavating ancient Mesopotamian sites, Lawrence met Gertrude Bell, who was to influence him during his time in the Middle East. In late 1911, Lawrence returned to England for a brief sojourn. By November he was en route to Beirut for a second season at Carchemish, where he was to work with Leonard Woolley. Prior to resuming work there, however, he briefly worked with Flinders Petrie atKafr Ammar in Egypt. Lawrence continued making trips to the Middle East as a field archaeologist until the outbreak of the First World War. In January 1914, Woolley and Lawrence were co-opted by the British military as an archaeological smokescreen for a British military survey of the Negev Desert. They were funded by the Palestine Exploration Fund to search for an area referred to in the Bible as the "Wilderness of Zin"; along the way, they undertook an archaeological survey of the Negev Desert. The Negev was of strategic importance, as it would have to be crossed by any Ottoman army attacking Egypt in the event of war. Woolley and Lawrence subsequently published a report of the expedition's archaeological findings,[17] but a more important result was an updated mapping of the area, with special attention to features of military relevance such as water sources. Lawrence also visited Aqaba and Petra. From March to May 1914, Lawrence worked again at Carchemish. Following the outbreak of hostilities in August 1914, Lawrence did not immediately enlist in the British Army; on the advice of S.F. Newcombe he held back until October, when he was commissioned on the General List. [edit]Arab revoltLawrence at Rabigh, north of Jeddah, 1917 Main article: Arab Revolt At the outbreak of the First World War Lawrence was a university post-graduate researcher who had for years travelled extensively within the Ottoman Empire provinces of the Levant (Transjordan and Palestine) and Mesopotamia (Syria and Iraq) under his own name. As such he became known to the Ottoman Interior Ministry authorities and their German technical advisors. Lawrence came into contact with the Ottoman-German technical advisers, travelling over the German-designed, -built, and -financed railways during the course of his research.[18] The Arab Bureau of Britain's Foreign Office conceived a campaign of internal insurgency against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East. The Arab Bureau had long felt it likely that a campaign instigated and financed by outside powers, supporting the breakaway-minded tribes and regional challengers to the Turkish government's centralised rule of their empire, would pay great dividends in the diversion of effort that would be needed to meet such a challenge. The Arab Bureau had recognised the strategic value of what is today called the "asymmetry" of such conflict. The Ottoman authorities would have to devote from a hundred to a thousand times the resources to contain the threat of such an internal rebellion compared to the Allies' cost of sponsoring it. With his first-hand knowledge of Syria, the Levant, and Mesopotamia, in 1914, Lawrence was posted to Cairo on the Intelligence Staff of the GOC Middle East.[19] The British government in Egypt sent Lawrence to work with the Hashemite forces in the ArabianHejaz in October 1916.[20] During the war, Lawrence fought with Arab irregular troops under the command of Emir Faisal, a son of Sherif Hussein of Mecca, in extended guerrilla operations against the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire. Lawrence obtained assistance from the Royal Navyto turn back an Ottoman attack on Yenbu in December 1916.[20] Lawrence's major contribution to the revolt was convincing the Arab leaders (Faisal and Abdullah) to co-ordinate their actions in support of British strategy. He persuaded the Arabs not to make a frontal assault on the Ottoman stronghold in Medina but allowed the Turkish army to tie up troops in the city garrison. The Arabs were then free to direct most of their attention to the Turks' weak point, the Hejaz railwaythat supplied the garrison. This vastly expanded the battlefield and tied up even more Ottoman troops, who were then forced to protect the railway and repair the constant damage. Lawrence developed a close relationship with Faisal, whose Arab Northern Army was to become the main beneficiary of British aid. Capture of Aqaba

Lawrence at Aqaba, 1917 In 1917, Lawrence arranged a joint action with the Arab irregulars and forces including Auda Abu Tayi (until then in the employ of the Ottomans) against the strategically located but lightly defended[22][23][24] town of Aqaba. On 6 July, after a surprise overland attack, Aqaba fell to Lawrence and the Arab forces. After Aqaba, Lawrence was promoted to major, and the new commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force,General Sir Edmund Allenby, agreed to his strategy for the revolt, stating after the war:

Lawrence now held a powerful position, as an adviser to Faisal and a person who had Allenby's confidence. Battle of TafilehIn January 1918, the battle of Tafileh, an important region southeast of the Dead Sea, was fought using Arab regulars under the command of Jafar Pasha al-Askari. The battle was a defensive engagement that turned into an offensive rout, and was described in the official history of the war as a "brilliant feat of arms".[26] Lawrence was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his leadership at Tafileh, and was also promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. By the summer of 1918, the Turks were offering a substantial reward for Lawrence's capture, with one officer writing in his notes; "Though a price of £15,000 has been put on his head by the Turks, no Arab has, as yet, attempted to betray him. The Sharif of Mecca [King of the Hedjaz] has given him the status of one of his sons, and he is just the finely tempered steel that supports the whole stunt structure of our influence in Arabia. He is a very inspiring gentleman adventurer." Fall of Damascus Lawrence was involved in the build up to the capture of Damascus in the final weeks of the war. Much to his disappointment, and contrary to instructions he had issued, he was not present at the city's formal surrender, arriving several hours after the city had fallen. Lawrence entered Damascus around 9am on 1 October 1918, but was only the third arrival of the day, the first being the 10th Australian Light Horse Brigade, led by Major A.C.N. 'Harry' Olden who formally accepted the surrender of the city from acting Governor Emir Said.[27] It has also been said that when Lawrence and his men entered the city they upset the local people by the way they were riding around town, shooting guns up in the air, and so forth. The Australians mounted their horses and confronted Lawrence and their men and 'silenced' them.[28] In newly liberated Damascus—which he had envisaged as the capital of an Arab state—Lawrence was instrumental in establishing a provisional Arab government under Faisal. Faisal's rule as king, however, came to an abrupt end in 1920, after the battle of Maysaloun, when the French Forces of General Gouraud, under the command of General Mariano Goybet, entered Damascus, destroying Lawrence's dream of an independent Arabia. Portrait of T. E. Lawrence byLowell Thomas During the closing years of the war he sought, with mixed success, to convince his superiors in the British government that Arab independence was in their interests. The secret Sykes-Picot Agreement between France and Britain contradicted the promises of independence he had made to the Arabs and frustrated his work.[29] In 1918 he co-operated with war correspondent Lowell Thomas for a short period. During this time Thomas and his cameraman Harry Chase shot a great deal of film and many photographs, which Thomas used in a highly lucrative film that toured the world after the war.

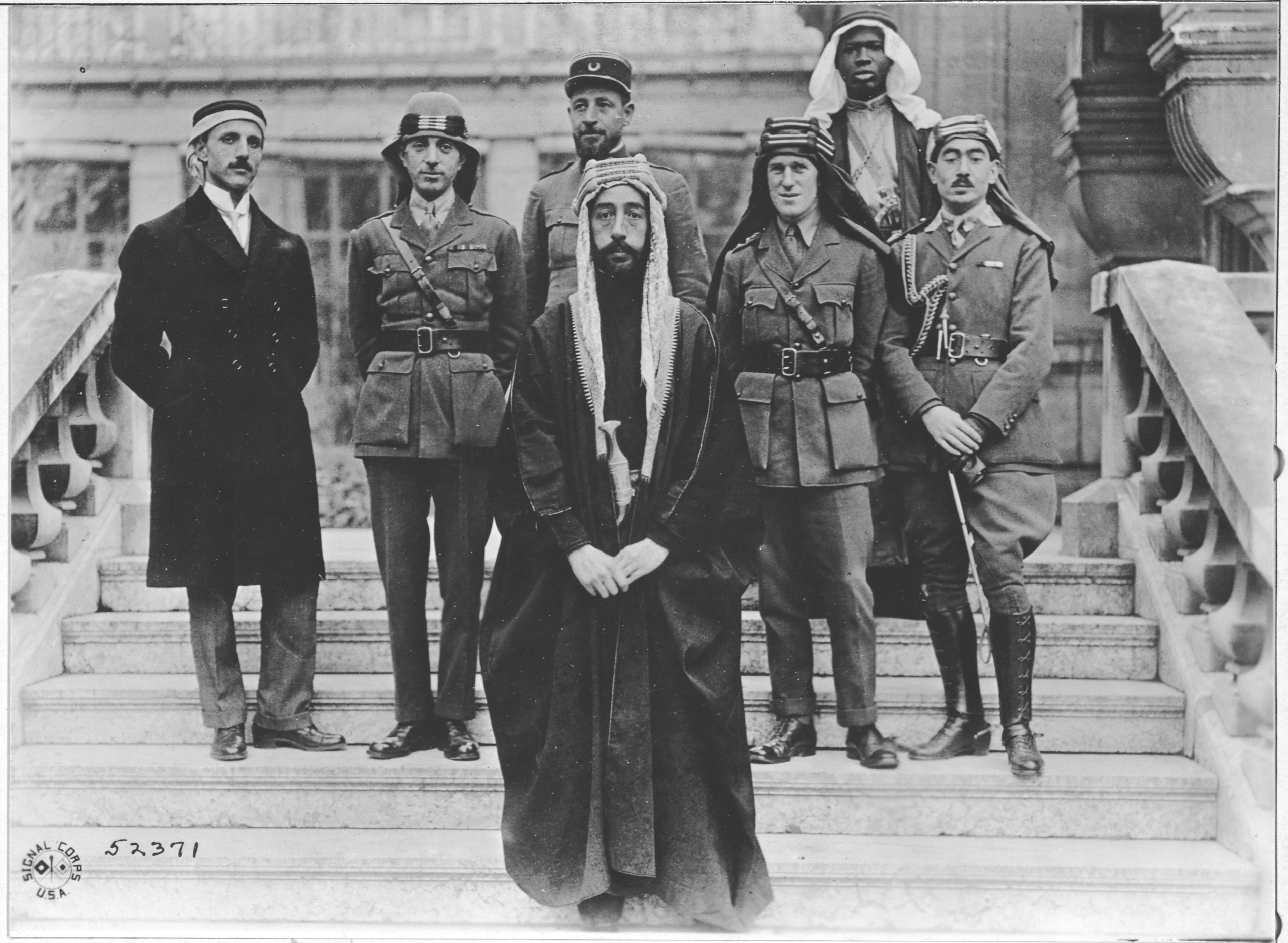

Postwar yearsEmir Faisal's party at Versailles, during the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. Left to right: Rustum Haidar, Nuri as-Said, Prince Faisal (front), Captain Pisani (rear), T. E. Lawrence, Faisal's slave (name unknown), Captain Hassan Khadri. Lawrence returned to the UK a full Colonel.[31] Immediately after the war, Lawrence worked for theForeign Office, attending the Paris Peace Conference between January and May as a member of Faisal's delegation. He served for much of 1921 as an advisor to Winston Churchill at the Colonial Office. On 17 May 1919, the Handley Page Type O carrying Lawrence on a flight to Egypt crashed at the airport of Roma-Centocelle. The pilot and co-pilot were killed; Lawrence came off with a broken shoulder blade and two broken ribs.[32] During his brief hospitalisation, he was visited by King Victor Emanuel III.[33] In August 1919, the American journalist Lowell Thomas launched a colourful photo show in London entitled With Allenby in Palestinewhich included a lecture, dancing, and music.[34] Initially, Lawrence played only a supporting role in the show, but when Thomas realized that it was the photos of Lawrence dressed as a Bedouin that had captured the public's imagination, he shot some more photos in London of him in Arab dress.[34] With the new photos, Thomas re-launched his show as With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia in early 1920; it was extremely popular.[34] Thomas' shows made Lawrence, who until then had been rather obscure, into a household name.[34] T. E. Lawrence, Emir Abdullah, Air Marshal Sir Geoffrey Salmond, Sir Herbert Samuel H.B.M. high commissioner and SirWyndham Deedes and others inJerusalem. In August 1922, Lawrence enlisted in the Royal Air Force as an aircraftman under the name John Hume Ross. The RAF recruiting officer who interviewed him was W. E. Johns, later to be well–known as the author of the Biggles series of novels. Johns rejected Lawrence's application, as he correctly believed it was under a false name, but was then ordered to accept Lawrence.[35][36] However, Lawrence was forced out of the RAF in February 1923 after being exposed. He changed his name to T. E. Shaw and joined the Royal Tank Corps in 1923. He was unhappy there and repeatedly petitioned to rejoin the RAF, which finally readmitted him in August 1925.[37] A fresh burst of publicity after the publication of Revolt in the Desert(see below) resulted in his assignment to a remote base in British India in late 1926, where he remained until the end of 1928. At that time he was forced to return to Britain after rumours began to circulate that he was involved in espionage activities. He purchased several small plots of land in Chingford, built a hut and swimming pool there, and visited frequently. This was removed in 1930 when the Chingford Urban District Council acquired the land and passed it to the City of London Corporation, but re-erected the hut in the grounds of The Warren, Loughton, where it remains, neglected, today. Lawrence's tenure of the Chingford land has now been commemorated by a plaque fixed on the sighting obelisk on Pole Hill. He continued serving in the RAF based at Bridlington, East Riding of Yorkshire, specialising in high-speed boats and professing happiness, and it was with considerable regret that he left the service at the end of his enlistment in March 1935. Lawrence was a keen motorcyclist, and, at different times, had owned seven Brough Superior motorcycles.[38] His seventh motorcycle is on display at the Imperial War Museum. Among the books Lawrence is known to have carried with him on his military campaigns is Thomas Malory's Morte D'Arthur. Accounts of the 1934 discovery of the Winchester Manuscript of the Morte include a report that Lawrence followed Eugene Vinaver—a Malory scholar—by motorcycle from Manchester to Winchester upon reading of the discovery in The Times.[39] Death

Lawrence's last Brough Superior,Imperial War Museum, London At the age of 46, two months after leaving the service, Lawrence was fatally injured in an accident on his Brough Superior SS100motorcycle in Dorset, close to his cottage, Clouds Hill, near Wareham. A dip in the road obstructed his view of two boys on their bicycles; he swerved to avoid them, lost control and was thrown over the handlebars.[40] He died six days later on 19 May 1935.[40]The spot is marked by a small memorial at the side of the road. Roadside Memorial tree and stone with engraving at Clouds Hill, Wareham, Dorset Lawrence on a Brough Superior SS100 One of the doctors attending him was the neurosurgeon Hugh Cairns who consequently began a long study of what he saw as the unnecessary loss of life by motorcycle dispatch riders through head injuries. His research led to the use of crash helmets by both military and civilian motorcyclists.[41] Moreton Estate, which borders Bovington Camp, was owned by family cousins, the Frampton family. Lawrence had rented and later bought Clouds Hill from the Framptons. He had been a frequent visitor to their home, Okers Wood House, and had for years corresponded with Louisa Frampton. With his body wrapped in the Union Flag, Lawrence's mother arranged with the Framptons for him to be buried in their family plot at Moreton.[42] His coffin was transported on the Frampton estate's bier. Mourners included Winston and Clementine Churchill, E. M. Forster and Lawrence's youngest brother, Arnold.[43] A bust of Lawrence was placed in the crypt at St Paul's Cathedral, London and a stone effigy by Eric Kennington remains in the Anglo-Saxon church of St Martin, Wareham inDorset.[44] [edit]WritingsThroughout his life, Lawrence was a prolific writer. A large portion of his output was epistolary; he often sent several letters a day. Several collections of his letters have been published. He corresponded with many notable figures, including George Bernard Shaw, Edward Elgar, Winston Churchill, Robert Graves, Noël Coward, E. M. Forster, Siegfried Sassoon, John Buchan, Augustus John and Henry Williamson. He met Joseph Conrad and commented perceptively on his works. The many letters that he sent to Shaw's wife, Charlotte, offer a revealing side of his character.[45] In his lifetime, Lawrence published four major texts. Two were translations: Homer's Odyssey, and The Forest Giant — the latter an otherwise forgotten work of French fiction. He received a flat fee for the second translation, and negotiated a generous fee plus royalties for the first. Further information: English translations of Homer#Lawrence [edit]Seven Pillars of Wisdom14 Barton Street, London S.W.1, where Lawrence lived while writing Seven Pillars. Lawrence's major work is Seven Pillars of Wisdom, an account of his war experiences. In 1919 he had been elected to a seven-year research fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford, providing him with support while he worked on the book. In addition to being a memoir of his experiences during the war, certain parts also serve as essays on military strategy, Arabian culture and geography, and other topics. Lawrence re-wrote Seven Pillars of Wisdom three times; once "blind" after he lost the manuscript while changing trains at Reading railway station. The list of his alleged "embellishments" in Seven Pillars is long, though many such allegations have been disproved with time, most definitively in Jeremy Wilson's authorised biography. However Lawrence's own notebooks refute his claim to have crossed the Sinai Peninsula from Aqaba to the Suez Canal in just 49 hours without any sleep. In reality this famous camel ride lasted for more than 70 hours and was interrupted by two long breaks for sleeping which Lawrence omitted when he wrote his book.[46] Lawrence acknowledged having been helped in the editing of the book by George Bernard Shaw. In the preface to Seven Pillars, Lawrence offered his "thanks to Mr. and Mrs. Bernard Shaw for countless suggestions of great value and diversity: and for all the present semicolons." The first public edition was published in 1926 as a high-priced private subscription edition, printed in London by Herbert John Hodgson and Roy Manning Pike, with illustrations by Eric Kennington, Augustus John, Paul Nash, Blair Hughes-Stanton and his wifeGertrude Hermes. Lawrence was afraid that the public would think that he would make a substantial income from the book, and he stated that it was written as a result of his war service. He vowed not to take any money from it, and indeed he did not, as the sale price was one third of the production costs.[47] This, along with his "saintlike" generosity, left Lawrence in substantial debt.[48] Revolt in the DesertPortrait of T. E. Lawrence byAugustus John, 1919 Revolt in the Desert was an abridged version of Seven Pillars, which he began in 1926 and was published in March 1927 in both limited and trade editions. He undertook a needed but reluctant publicity exercise, which resulted in a best-seller. Again he vowed not to take any fees from the publication, partly to appease the subscribers to Seven Pillars who had paid dearly for their editions. By the fourth reprint in 1927, the debt from Seven Pillars was paid off. As Lawrence left for military service in India at the end of 1926, he set up the "Seven Pillars Trust" with his friend D. G. Hogarth as a trustee, in which he made over the copyright and any surplus income of Revolt in the Desert. He later told Hogarth that he had "made the Trust final, to save myself the temptation of reviewing it, if Revolt turned out a best seller." The resultant trust paid off the debt, and Lawrence then invoked a clause in his publishing contract to halt publication of the abridgment in the UK. However, he allowed both American editions and translations, which resulted in a substantial flow of income. The trust paid income either into an educational fund for children of RAF officers who lost their lives or were invalided as a result of service, or more substantially into the RAF Benevolent Fund. [edit]PosthumousLawrence left unpublished The Mint,[49] a memoir of his experiences as an enlisted man in the Royal Air Force. For this, he worked from a notebook that he kept while enlisted, writing of the daily lives of enlisted men and his desire to be a part of something larger than himself: the Royal Air Force. The book is stylistically very different from Seven Pillars of Wisdom, using sparse prose as opposed to the complicated syntax found in Seven Pillars. It was published posthumously, edited by his brother, Professor A. W. Lawrence. After Lawrence's death, A. W. Lawrence inherited Lawrence's estate and his copyrights as the sole beneficiary. To pay the inheritance tax, he sold the U.S. copyright of Seven Pillars of Wisdom (subscribers' text) outright to Doubleday Doran in 1935. Doubleday still controls publication rights of this version of the text of Seven Pillars of Wisdom in the USA. In 1936 Prof. Lawrence split the remaining assets of the estate, giving Clouds Hill and many copies of less substantial or historical letters to the nation via the National Trust, and then set up two trusts to control interests in T. E. Lawrence's residual copyrights. To the original Seven Pillars Trust, Prof. Lawrence assigned the copyright in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, as a result of which it was given its first general publication. To the Letters and Symposium Trust, he assigned the copyright in The Mint and all Lawrence's letters, which were subsequently edited and published in the book T. E. Lawrence by his Friends (edited by A. W. Lawrence, London, Jonathan Cape, 1937). A substantial amount of income went directly to the RAF Benevolent Fund or for archaeological, environmental, or academic projects. The two trusts were amalgamated in 1986 and, on the death of Prof. A. W. Lawrence in 1991, the unified trust also acquired all the remaining rights to Lawrence's works that it had not owned, plus rights to all of Prof. Lawrence's works. Bibliography

[edit]SexualityLawrence's biographers have discussed his sexuality at considerable length, and this discussion has spilled into the popular press.[51] There is no reliable evidence for consensual sexual intimacy between Lawrence and any person. His friends have expressed the opinion that he was asexual,[52][53] and Lawrence himself specifically denied, in multiple private letters, any personal experience of sex.[54] While there were suggestions that Lawrence had been intimate withDahoum, who worked with Lawrence at a pre-war archaeological dig in Carchemish,[55] and fellow-serviceman R.A.M. Guy,[56] his biographers and contemporaries have found them unconvincing.[55][56][57] The dedication to his book Seven Pillars is a poem entitled "To S.A." which opens:

Lawrence was never specific about the identity of "S.A." There are many theories which argue in favour of individual men, women, and the Arab nation.[58] The most popular is that S.A. represents (at least in part) his companion Selim Ahmed, "Dahoum", who apparently died of typhus prior to 1918. Although Lawrence lived in a period during which official opposition to homosexuality was strong, his writing on the subject was tolerant. In Seven Pillars, when discussing relationships between young male fighters in the war, he refers on one occasion to "the openness and honesty of perfect love"[59] and on another to "friends quivering together in the yielding sand with intimate hot limbs in supreme embrace".[60] In a letter to Charlotte Shaw he wrote "I've seen lots of man-and-man loves: very lovely and fortunate some of them were."[61] In both Seven Pillars and a 1919 letter to a military colleague,[62] Lawrence describes an episode in November 1917 in which, while reconnoitring Dera'a in disguise, he was captured by the Ottoman military, heavily beaten, and sexually abused by the local Bey and his guardsmen. The precise nature of the sexual contact is not specified. Although there is no independent evidence, the multiple consistent reports, and the absence of evidence for outright invention in Lawrence's works, make the account believable to his biographers.[63] At least three of Lawrence's biographers (Malcolm Brown, John Mack, and Jeremy Wilson) have argued this episode had strong psychological effects on Lawrence which may explain some of his unconventional behaviour in later life. There is considerable evidence that Lawrence was a masochist. In his description of the Dera'a beating, Lawrence wrote "a delicious warmth, probably sexual, was swelling through me", and also included a detailed description of the guards' whip in a style typical of masochists' writing.[64] In later life, Lawrence arranged to pay a military colleague to administer beatings to him,[51] and to be subjected to severe formal tests of fitness and stamina.[65] While John Bruce, who first wrote on this topic, included some other claims which were not credible, Lawrence's biographers regard the beatings as established fact.[66] John E. Mack sees a possible connection between T.E.'s masochism and the childhood beatings he had received from his mother[67] for routine misbehaviours.[68] His brother Arnold thought the beatings had been given for the purpose of breaking T.E.'s will.[68] Writing in 1997, Angus Calder noted that it is "astonishing" that earlier commentators discussing Lawrence's apparent masochism and self-loathing failed to consider the impact on Lawrence of having lost his brothers Frank and Will on the Western front, along with many other school friends. The commencement of discussions about Middle East situation with Britain can be traced back to the rule of Sharif Hussein ibn Ali of the Hashemite family, who were claimants of the descendents of Prophet Muhammad SAW and guardian of Hijaz. The basis of the Middle East conflict and resulting tension in the 20th Century can be found in the events surrounding First World War. Amir Abdullah, son of Sharif Hussein, paid a visit to the British consul general and agent positioned in Egypt in February 1914 to inquire about the support that Arabs can get from Britain should his father launch a revolt against Ottoman Turks. However, Abdullah received a non-committal response from Lord Kitchener as there was no war between Germany and Britain and no former alliance was formed between Germany and Turkey till yet. On the outbreak of war in August 1914 and after witnessing the deteriorating situation of British military fortunes in Middle East in 1915, Kitchener sought a clever move of asking Arab support from the leader of the Arabs indebted to Britain, promising the transfer of the Islamic caliphate to Hussein. A comprehensive correspondence was held between Sharif Hussein and his two sons, Abdullah and Faysal from January 1915 to January 1916 in Cairo with the British high commissioner, Sir Henry McMohan. Abdullah and Faysal, later kings of Jordan and Syria respectively, were to play a significant part in the subsequent events as well. Hussein wrote a letter to McMohan; with an enclosed letter from Abdullah dated July 14, 1915; specifying the areas he wished to be included in the “Sharifian Arab Government” after Arab independence. Hussein’s proposed land included the Arabian Peninsula other than Aden, Palestine, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. In his response to Hussein’s letter, McMohan agreed to post-war Arab independence on behalf of the British Government, limited only by the constraints and reservations of non-Arab territories or related to what Britain was not at liberty “to act without detriment to the interests of her ally, France”. “The districts of Mersin and Alexandretta, and portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo” were the territories not assessed as Arab by the British. As the exact meaning couldn’t be derived from this, similar to the later Balfour Declaration, Arab spokesmen has asserted since the time of the correspondence that Palestine was included in the proposed Arab Peninsula. Sharif Hussein saw this opportunity to liberate Arab lands from the oppression of Turks, who had abandoned their pluralistic and pan-Islamic policies to launch a secular Turkish nationalism, launched the Great Arab Revolt on June 5, 1915, trusting the word of British officials who promised Arabs a unified state. As the head of Arab nationalist, with his alliance of Britain and France, the Great Arab Revolt was initiated by Sharif Hussein, with the Arab armies led by his sons. Emir Faysal liberated Damascus from Ottoman rule in 1918 and till the end of the war; Arab forces had taken control of most of the Arabian Peninsula, Southern Syria and all of the modern Jordan. Britain walked out on its promise after the conclusion of the war, denying Arabs the promised unified Arab state. And while Arabs did not get what they aimed for, it was nevertheless a demonstration of the effectiveness of Royal Hashemite family that they were able to secure a rule over Arabia, Iraq and Transjordan because of the Great Arab Revolt. He loved history and travel, spending his youth exploring castles and old churches. After a study trip in Syria where he walked over a thousand miles to study remote Crusader castles, Lawrence graduated with first-class honors and decided to become an archaeologist. With the Allied victory came disappointment for the Arabs, when they were finally informed of Britain and France's decision regarding the future of Syria.

St Nicolas Church, Moreton, Dorset -St Nicholas Church at Moreton, in Dorset, has several claims to fame; it is associated with the Frampton family, it was chosen for the funeral of Lawrence of Arabia and it is possibly the only church in the UK which has exclusively engraved glass rather than coloured or stained glass. The Framptons had been associated with the area since the 14th century and it was a Frampton who persecuted the Tolpuddle Martyrs for organising a trade union in the 19th century. Lawrence of Arabia was friendly with the later Framptons and even rented (and later bought) his nearby Clouds Hill home from the Framptons before his death in a motorcycle accident in 1935.

|

|

|

The title comes from the Book of Proverbs, 9:1: "Wisdom hath builded her house, she hath hewn out her seven pillars" (KJV). Prior to the First World War, Lawrence had begun work on a scholarly book about seven great cities of the Middle East, to be titled Seven Pillars of Wisdom. When war broke out, it was still incomplete and Lawrence stated that he ultimately destroyed the manuscript although he remained keen on using his original title 'Seven Pillars of Wisdom' for his later work. the book had to be rewritten three times - once blind, following the loss of the manuscript on a train at Reading. The Seven Pillars' rock formation in Wadi Rum 'Seven Pillars of Wisdom' is a biographical account of his experiences during the Arab Revolt of 1917–18, when Lawrence was based in Wadi Rum (now a part of Jordan) as a member of the British Forces of North Africa. Together with the support of Emir Faisal and his tribesmen he prepared attacks on the Ottoman forces from Aqaba in the south to Damascus in the north (Syria). Many sites inside the Wadi Rum area have been named after Lawrence to attract tourists, although there is little or no evidence connecting him to any of these sites, these include the famous rock formations near the entrance known as 'The Seven Pillars'. Speculation surrounds the dedication of the book which is a poem that was penned by Lawrence and edited by Robert Graves. the speculation ranges from it being about individuals to being about the whole Arab Race. It begins 'To S.A' which it is widely agreed was most probably Selim Ahmed (Dahoum) Selim Ahmed). A young Arab boy from Syria of whom Lawrence was very fond and who died an untimely death probably from typhus at the age of 19, just weeks before Lawrence's offensive to liberate Damascus. Lawrence received the news just days before he entered Damascus and it was there that he was to fight his most aggressive and furious battle of all.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment