War with China: Are we closer than we think? | Under Investigation

It’s really hard to see a way not to get militarily involved in this now. It really does feel like the only three options are appeasement so they get to continue to build wherever they want and treat their people the way they do, allowing them to invade other nations over illegal sovereign claims, or military action against them. And although the last one seems most likely to work, it’s hard to see it not spiralling out of control into a full-scale war. I only hope when or if that happens that we can all rely on our fellow European and Asian allies to work together against China.

In May and June of this year, Chinese warships took turns appearing outside the first island chain, including the Liaoning aircraft carrier in eastern Taiwan and Okinawa waters. The specific method of the CCP’s Anti-Access and Area Denial is to attack the U.S. aircraft carrier formation so that it does not dare to approach China’s surrounding waters easily. In June and July, the U.S. military launched counterattacks in the East China Sea and the South China Sea in response to the CCP's weaknesses. It made clear that the Indo-Pacific strategy has become a priority for the U.S. in recent years.

The U.S. is preparing war with China and Russia at the same time

Fighting two wars at the same time

In the eyes of the U.S., China and Russia are the two most important adversaries: their vast territory, long history, profound national culture, and strategic nuclear weapons are all threats to American global hegemony. According to the U.S., the only way to eliminate the threat is that the two great powers’ submit to U.S.’ global hegemony. As regards Russia, which has yet to recover from its weakness, the U.S. hopes to completely dismantle it and destroy its nuclear weapons, causing it to lose all global influence. As regards China, which has a more united people, a more stable ruling party, and a healthier economy, the U.S. hopes to overthrow its leaders through a “color revolution” and gradually erode the Chinese people’s faith in communism. Maintaining military containment of both countries is, in Kroenig’s view, a non-negotiable premise.

Another proposal is to include U.S. “key allies in military planning, sharing responsibilities, and streamlining the division of labor for weapons procurement”. With the U.S. and its formal treaty allies accounting for nearly 60% of global GDP, Kroenig suggests that the U.S. supplement existing alliances (e.g., NATO, bilateral alliances in Asia) with new arrangements like the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) to “more easily mobilize resources and maintain military superiority over China and Russia”. He suggested that U.S. European allies invest in armor and artillery, while Asian allies purchase mines, harpoon missiles, and submarines, and the U.S. Army prioritizes Europe while the U.S. Navy handles the Indo-Pacific.

The current U.S. policy towards Russia is not a blip on the radar, but a continuation of a decades-long Cold War strategy. In 1972, shortly after Kissinger’s secret visit to China, he told President Nixon that the Chinese were “just as dangerous as the Russians, and even more dangerous in certain historical periods”. He hoped that Washington could take advantage of Moscow and Beijing by playing “an unemotional balance of the power game”. In Kissinger’s view, 20 years later, the U.S. would lean towards Russia to restrain China, if it could first use China to weaken the Soviet Union. Subsequent U.S. administrations (both Democrat and Republican) followed through on this strategy, working with China and weakening the Soviet Union, hastening its collapse.

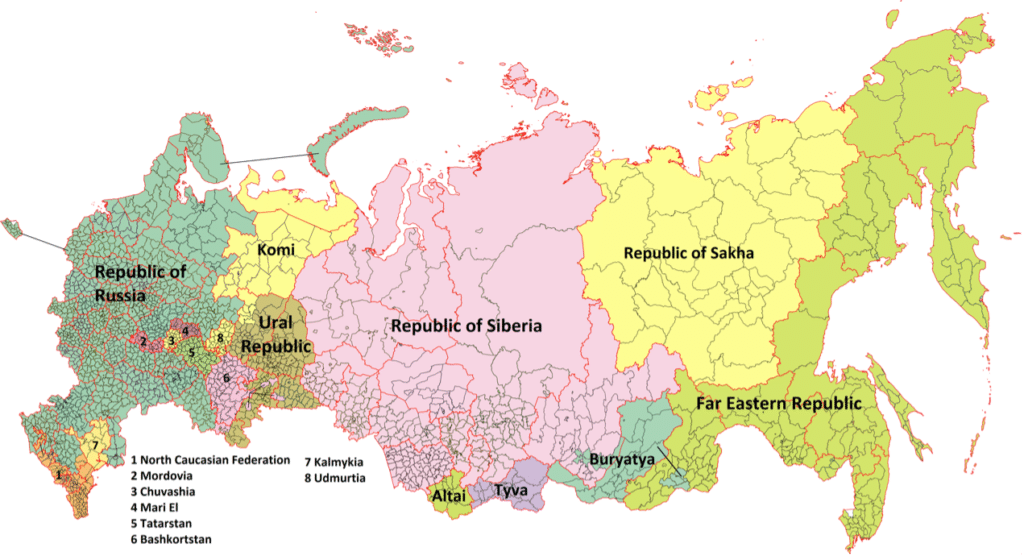

But the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 did not fully satisfy the U.S. During Yeltsin’s administration, the U.S. failed to persuade Russia—like Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan—to give up its nuclear weapons altogether. After the U.S. withdrew from the 1972 ABM Treaty in 2001, Russia also withdrew from the START II Treaty. At this time, Russia still deployed more than 5,000 strategic nuclear warheads and maintained a strong influence in Eastern Europe. The goal of the U.S. is to further weaken or destroy Russia economically, destabilize its politics, confuse the Russian people, and eventually dismantle Russia into smaller countries, and most importantly, eliminate its nuclear arsenal.

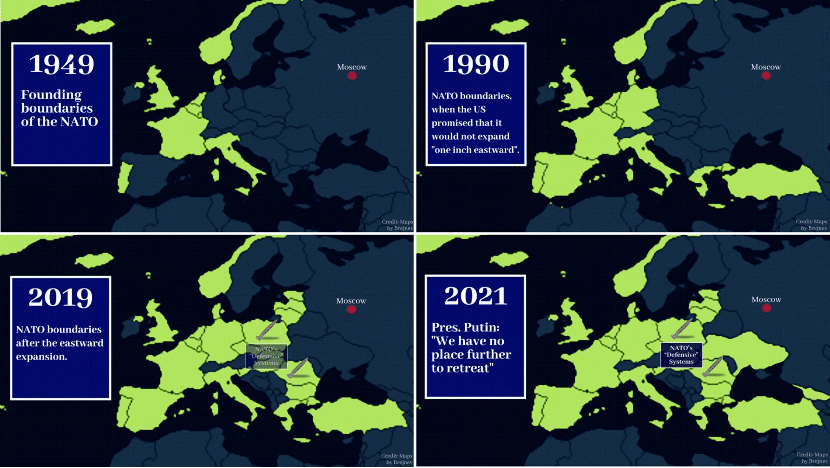

NATO’s eastward expansion has pushed the security issue in Ukraine to a boiling point. Prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, the U.S. promised Mikhail Gorbachev that NATO would not expand eastward because its original mission—to confront the Soviet Union and contain communism in Europe—had come to an end when the Cold War ceased. However, NATO reneged on this “gentleman’s agreement” after the Cold War by adopting 14 more member countries, including some former members of the Soviet Union. In 2018, Ukraine amended its constitution to make attaining NATO and EU membership its primary national strategy, which posed a serious threat to Russia’s national security. As Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital, is only 760 kilometers in a straight line from Moscow, giving permission to NATO to deploy ultra-high-sonic nuclear weapons in Ukraine would almost certainly mean the total military surrender of Russia.

NATO’s Eastward Expansion.

The United States discarded its oft-misunderstood “two war” doctrine, intended as a template for providing the means to fight two regional wars simultaneously, late last decade. Designed to deter North Korea from launching a war while the United States was involved in fighting against Iran or Iraq (or vice versa,) the idea helped give form to the Department of Defense’s procurement, logistical and basing strategies in the post–Cold War, when the United States no longer needed to face down the Soviet threat. The United States backed away from the doctrine because of changes in the international system, including the rising power of China and the proliferation of highly effective terrorist networks.

But what if the United States had to fight two wars today, and not against states like North Korea and Iran? What if China and Russia sufficiently coordinated with one another to engage in simultaneous hostilities in the Pacific and in Europe?

Political Coordination

Could Beijing and Moscow coordinate a pair of crises that would drive two separate U.S. military responses? Maybe, but probably not. Each country has its own goals, and works on its own timeline. More likely, one of the two would opportunistically take advantage of an existing crisis to further its regional claims. For example, Moscow might well decide to push the Baltic States if the United States became involved in a major skirmish in the South China Sea.

In any case, the war would start on the initiative of either Moscow or Beijing. The United States enjoys the benefits of the status quo in both areas, and generally (at least where great powers are concerned) prefers to use diplomatic and economic means to pursue its political ends. While the U.S. might create the conditions for war, Russia or China would pull the trigger.

On the upside, only some of the requirements for fighting in Europe and the Pacific overlap. As was the case in World War II, the U.S. Army would bear the brunt of defending Europe, while the Navy would concentrate on the Pacific. The U.S. Air Force (USAF) would play a supporting role in both theaters.

Russia lacks the ability to fight NATO in the North Atlantic, and probably has no political interest in trying. This means that while the United States and its NATO allies can allocate some resources to threatening Russia’s maritime space (and providing insurance against a Russian naval sortie,) the U.S. Navy (USN) can concentrate its forces in the Pacific. Depending on the length of the conflict and the degree of warning provided, the United States could transport considerable U.S. Army assets to Europe to assist with any serious fighting.

The bulk of American carriers, submarines and surface vessels would concentrate in the Pacific and the Indian Oceans, fighting directly against China’s A2/AD system and sitting astride China’s maritime transit lanes. Long range aviation, including stealth bombers and similar assets, would operate in both theaters as needed.

The U.S. military would be under strong pressure to deliver decisive victory in at least one theater as quickly as possible. This might push the United States to lean heavily in one direction with air, space and cyber assets, hoping to achieve a strategic and political victory that would allow the remainder of its weight to shift to the other theater. Given the strength of U.S. allies in Europe, the United States might initially focus on the conflict in the Pacific.

Alliance Structure

U.S. alliance structure in the Pacific differs dramatically from that of Europe. Notwithstanding concern over the commitment of specific U.S. allies in Europe, the United States has no reason to fight Russia apart from maintaining the integrity of the NATO alliance. If the United States fights, then Germany, France, Poland and the United Kingdom will follow. In most conventional scenarios, even the European allies alone would give NATO a tremendous medium term advantage over the Russians; Russia might take parts of the Baltics, but it would suffer heavily under NATO airpower, and likely couldn’t hold stolen territory for long. In this context, the USN and USAF would largely play support and coordinative roles, giving the NATO allies the advantage they needed to soundly defeat the Russians. The U.S. nuclear force would provide insurance against a Russian decision to employ tactical or strategic nuclear weapons.

The United States faces more difficult problems in the Pacific. Japan or India might have an interest in the South China Sea, but this hardly guarantees their participation in a war (or even the degree of benevolence of their neutrality.) The alliance structure of any given conflict would depend on the particulars of that conflict; any of the Philippines, Vietnam, South Korea, Japan or Taiwan could become China’s primary target. The rest, U.S. pressure aside, might well prefer to sit on the sidelines. This would put extra pressure on the United States to establish dominance in the Western Pacific with its own assets.

Parting Shots

The United States can still fight and win two major wars at the same time, or at least come near enough to winning that neither Russia nor China would see much hope in the gamble. The United States can do this because it continues to maintain the world’s most formidable military, and because it stands at the head of an extremely powerful military alliance. Moreover, Russia and China conveniently pose very different military problems, allowing the United States to allocate some of its assets to one, and the rest to the other.

However, it bears emphasis that this situation will not last forever. The United States cannot maintain this level of dominance indefinitely, and in the long-term will have to choose its commitments carefully. At the same time, the United States has created an international order that benefits many of the most powerful and prosperous countries in the world; it can count on their support, for a while.

No comments:

Post a Comment