THE KNIGHT TEMPLARS: The Third Crusade

BeynacThe secret world of the Knights Templar revealed: Caverns used by the shadowy warrior monks 700 years ago are just a few feet inside a rabbit hole

Once used as a ceremonial spot for the followers of a secretive religious sect, these are the underground caves offering safe haven after leaders of the free world brutally dismantled the group's power base.

The caves in Shropshire were once a place of pilgrimage and worship for followers of the Knights Templar, a feared fighting force during the Crusades who built an international power base on their reputation and spoils.

The untouched caverns date back to a time when the Knights were prominent before King Philip IV of France, fearful of their power and deeply in their debt, attempted to dismantle the renowned group.

Many were tortured into confessions and burnt at the stake in order to publicly discredit them, but after they were literally forced underground, caves such as those in Shropshire offered haven to members and followers.

The Caynton Caves lay untouched for years and it is still not known exactly when they were carved. Some believe it was by their knights 700 years ago while some think it was by their followers in the 17th century.

In recent times they have been used by numerous groups including druids and pagans wishing to find a safe place to worship, as the Templar's followers had used it for centuries ago.

Although they were closed up five years ago after the landowners became sick of the constant requests and found the caves strewn with litter and new carvings, adding to the crosses etched in the walls from long ago.

Photographer Michael Scott, from Birmingham, 33, captured the eerie pictures of the inside for the first time since it was shut in 2012. He said: 'I traipsed over a field to find it, but if you didn't know it was there you would just walk right past it. It's probably less than a metre underground, so it's more into the field than under it.

'Considering how long it's been there it's in amazing condition, it's like an underground temple.'

Shadowy: Once used as a ceremonial spot for the followers of a secretive religious sect, these are the underground caves offering safe haven after leaders of the free world brutally dismantled the group's power base

Historic: The caves in Shropshire were once a place of pilgrimage and worship for followers of the Knights Templar, a feared fighting force during the Crusades who built an international power base on their reputation and spoils

Enlightened: Sunlight rushes in through the small openings in the caves, just metres under the surface of the ground in Shropshire, once used by followers of the Knights Templar (right, stock image) that made its name in the Crusades

Forced underground: The untouched caverns date back to a time when the Knights were prominent before King Philip IV of France, fearful of their power and deeply in their debt, attempted to dismantle the renowned group

Scratching the surface: The entrances to the caves look barely bigger than rabbit holes when seen from the ground above but below is an intricate underground cavern

Born again: In recent times they have been used by numerous groups including druids and pagans wishing to find a safe place to worship, as the Templar's followers had used it for centuries ago

Casting a shadow: The caves were closed up five years ago after the landowners became sick of the constant requests and found the caves strewn with litter and new carvings, adding to the crosses etched in the walls from years gone by

Light it up: Photographer Michael Scott, from Birmingham, set out in search of the historical wonder after seeing a video of it online and captured the eerie pictures of the inside for the first time since it was shut in 2012

Holy place: Inside the caves, as well as plenty of places to rest candles, there is what appears to be a basic stone altar on the wall on the right

Hole in the wall: The intricately carved caves feature cleverly engineered pillars to hold the weight and make them safe for the worshipers inside, as well as ornate archways and squares

Lost in time: The Caynton Caves lay untouched for years and it is still not known exactly when they were carved. Some believe it was by their knights 700 years ago while some think it was by their followers in the 17th century

Safe haven: In recent times they have been used by numerous groups including druids and pagans wishing to find a safe place to worship, as the Templar's followers had used it for centuries ago.

See the light: The caves add fuel to the widely held view that the Templar were not disbanded in the 14th century after being attacked by the French king, but instead went underground and still exert control within many powerful organisatio

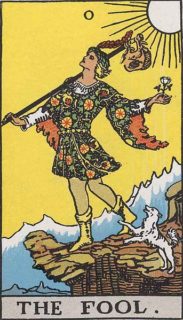

The Fool is a powerful Tarot card because its possibilities all start in nothingness and reach into infinity

On Friday October 13, 1307 the French King Philip IV, who was deeply indebted to the Knights Templar, ordered them arrested and charged with heretical practices and on November 22 of that year under pressure from Philip, Pope Clement V issued the papal bull Pastoralis Praeeminentiae instructing all the monarchs of Europe to seize their assets.

Whether or not the Knights Templar practiced heretical beliefs as charged, the immolation of Templar Grand Master Jacques de Molay at the hands of the Pope’s Inquisitors in 1314 would serve as an inspiration to generations of people who did.

Pope Innocent III’s brutal Albigensian Crusade of 1209-29 against the powerful dualist Cathar movement pitted Northern France’s Catholic nobility against the lesser nobility of the south who were tolerant and supportive of it.

As a pre-Christian faith deeply rooted in the ancient world and spread by Rome’s legions through Mithraism to the four corners of the pagan Roman Empire, Catharism represented an old and powerful belief system which refused to be suppressed by the sterile and often contradictory doctrines of Rome’s Christian Empire.

As described by Reverend V.A. Demant, Canon of London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral in a preface to a 1947 book on the subject titled The Arrow and the Sword:

“To mention only its roots in Mithraism, its links with the Gnostics, its theological dualism, its asceticism, the ritual of life and death as cosmic mysteries, the appeal of the troubadours, Arthurian legends and the cult of the Holy Grail, the passions aroused for and against witchcraft, the intimate connection between sex and religion — all these things are sufficient testimony to the deep rooted vitality of a stream of religious consciousness which cannot be superciliously dismissed by rationalists and moralists.”

Writing on the heels of World War II, and with Europe still in ruins from the rise of an irrational and immoral pagan faith called Nazism, Demant feared that such a vital apocalyptic belief system with its “robust religiousness” and commitment to a struggle against an evil material world was bound to rise again, as it had so many times in the past.

Yet, he might not have been surprised to know that his own “Protestant” faith, of which he was a senior officer as the Canon of St. Paul’s, had its own roots in the same heresy.

Now lost in the cross weaves of history, Britain’s version of the heresy represented a new and far more dangerous version of life-denying Catharism than was ever imagined by the Templars, Bernard of Clairvaux or Jacques DeMolay.

| Torture of the Templars: Knights known for their blood-crazed bravery were butchered by a French king who accused them of sexual depravity and devil worship, book claims

The times were medieval but there was something surprisingly modern about the way the scandal broke - via a low-life with a salacious story to sell to the highest bidder.

The man's name was Esquin and he came from south-west France, where, for some routine misdemeanour, he had been locked up in prison with a cellmate who kept him entertained with tales of profane goings-on among warrior monks from a secretive order known as the Knights Templar.

Originally, they had been set up to protect Christian pilgrims travelling to the Holy Land.

In a co-ordinated dawn action on Friday, October 13, 1307, the king's men raided every religious house belonging to the unsuspecting Templars from Normandy to Toulouse

The man had been a member of the order and told of indulging in blasphemy, devil-worship and initiation ceremonies that involved intimate kissing and much more besides.

Esquin knew the Templars had opponents in high places who would pay handsomely for such inside information. So, once he was freed, he first approached a contact in the entourage of the King of Aragon, in Spain, offering his story for 3,000 livres (pounds) cash and a further 1,000 every year once it was verified. He was sent packing.

Then he took his tittle-tattle to the court of the King of France, Philip IV. And there he struck gold.

Philip was a money-grabbing monarch who had already filled his royal coffers by shaking down the Jews in his kingdom for their silver and expelling them. Now he had set his avaricious sights on the vast wealth the Templars were known to possess.

He had ordered a secret dossier to be compiled on them and Esquin was exactly the sort of whistleblower his spies had been dying to find.

With his allegations of depravity to work from, they launched a full-on witch-hunt and over the next two years unearthed more moles and compiled more damning and lurid gossip from disgruntled members of the order who had been expelled or otherwise left under a cloud.

Then they pounced on their prey. In a co-ordinated dawn action on Friday, October 13, 1307, the king's men raided every premises and religious house belonging to the unsuspecting Templars from Normandy to Toulouse.

Torture of the Knights Templars, organized by Guillaume de Nogaret under King Philip IV (1285-1314)

They were seized on the pretext, as the royal warrant said, of being 'wolves in sheep's clothing, vilely insulting our religious faith'.

They were denounced as 'a disgrace to humanity, a pernicious example of evil and a universal scandal'. Rounded up en masse, they were charged with the sins of sodomy, heresy and anything else that would cause outrage and disgust and puncture their image of holiness and righteousness. All their possessions were seized.

Yet as broadcaster and medieval history expert Dan Jones reveals in a new book tracing the story of this mysterious sect, the Templars were innocent of the charges Esquin had laid against them.

At the heart of the allegations was nothing more than the so-called 'kiss of peace' that the knights openly admitted giving to initiates, often on the lips.

This was translated into a ceremony of orgiastic depravity in which they stood naked to kiss each other all over, including on the backside. Black magic — 'offerings to idols' — was also alleged.

In a remarkably short time, an order of knights which had fought the cause of Christendom for nearly two centuries was ruthlessly crushed out of existence.

This was done not by the Muslims — sworn enemies whom the Knights Templar had slaughtered in their hundreds of thousands — but by the order's fellow Christians, who might have been expected to back them.

By the third decade of the 14th century, the battling Templars were no more.

But who exactly were these persecuted 'holy' knights with distinctive red crosses on their shields? And why have they remained a subject of fascination even into the 21st century, when they have been presented variously as heroes, martyrs, thugs, bullies, victims, criminals, perverts, heretics, depraved subversives, guardians of the Holy Grail and protectors of Christ's secret bloodline?

Jacques DeMolay was the twenty-third and last Grand Master of the Knights Templar

In his book, Dan Jones informs us that the sect — dubbed God's holy warriors — was founded in 1119 with the specific task of protecting European pilgrims who journeyed to the Holy Land in the Middle East to visit Christian shrines.

As a semi-monastic order, they took vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. Their name came from the temple in Jerusalem, which was their shrine.

They then became the leading arm of the Crusades, those gruesome religious wars in which Christian kings aimed to wrest the homeland of Jesus Christ from Islamic rule. Much of their history is therefore a long succession of battles and massacres in which heads were lopped off by the thousand and blood was spilt in profusion on both sides.

In those days jihad — holy war — was a clash of mutual hate and destruction in which both sides revelled in their task of 'exterminating the perfidious pagans' and little quarter was given. The English crusader King Richard the Lionheart — wearing on his tunic the red cross of the Templars — thought nothing of summarily slaughtering 2,600 Muslim prisoners outside the town of Acre in a fit of pique.

There were terrible sieges that dragged on until the desperate defenders were starved into submission. At the port of Damietta on the Nile estuary, crusaders finally forced their way in after two years to find 'streets strewn with bodies of the dead, wasting away from pestilence and famine'. The smell 'was too much for most people to bear'.

Nevertheless, the victors held their noses and went about God's business, plundering gold, silver, silks and slaves, and grabbing 500 surviving children who were forcibly baptised into Christianity.

But the Muslim forces had their revenge with a particularly vicious weapon called 'Greek fire' — a sticky resin in pots that could be hurled, grenade-style, by catapults. It burst into flame on impact and clung to clothing. The crusaders were terrified of it.

An English knight, fighting on foot after his horse was killed under him, was hit directly with a burning missile which set alight his coat, the flames searing his face and then his whole body, 'as if he had been a cauldron of pitch'.

In all this blood-letting, the Templars proved notably good at their job — disciplined, ruthless, fearless and sworn to die rather than surrender. In one battle against the Muslim leader Saladin, 140 knights, shouting out in unison 'Christ is our life and death is our reward', charged 7,000 Saracens and 'died in a shower of their own gore'.

On another occasion, Templar knights barrelled into the narrow streets of a town in pursuit of a fleeing Muslim army, only to find they had run into a trap and were outnumbered and surrounded. In savage hand-to-hand fighting, one knight's nose was sliced so badly that it hung loose by his mouth.

Blood flowed freely 'like a freshly tapped barrel of wine' as nearly 600 knights died in the savage street-fighting.

Because of deeds such as this the Templars quickly became semi-legendary figures, featuring in popular stories, works of art, ballads and histories.

The Templars quickly became semi-legendary figures, featuring in popular stories, works of art, ballads and histories

Such was the potency of the myth that grew around them that an admirer even cut off the genitals of a Templar killed in battle 'and kept them for begetting children so that, even when dead, the man's member might produce an heir with courage as great as his'.

As a result of their fame and dedication to God's work, charitable funds and bequests of money and property rolled into their coffers. And their wealth snowballed, as they had the special protection of the Pope and were exempted from the rules and taxes that monarchs imposed on everyone else.

Soon, Templars could be found across vast swathes of Europe and beyond — from the battlefields of Palestine, Syria and southern Spain to towns and villages in Italy and especially France, where they managed extensive estates to fund their military adventures.

In England they owned manor houses, sheep farms, watermills, churches, markets, forests and fairs in almost every county.

Such vast riches gave them influence, and they numbered kings and queens, patriarchs and popes among their friends and supporters. England's Henry II used the Templars as a bank, depositing coins, jewels and valuable trinkets with them, while knights were seconded to his court as diplomats.

Their tentacles were everywhere.The order helped finance wars, loaned money, collected taxes, built castles, ran cities, ports and fleets of ships, raised armies, interfered in trade disputes and carried out political assassinations.

Although there were rarely more than 1,000 knights at any one time, they became, in Jones's words, 'as mighty an outfit as existed during the later Middle Ages'.

And that inevitably brought them enemies.

To some of their more pious contemporaries, their constant wars were a corruption of the supposedly peaceful principles of Christianity. Others thought them dangerously unaccountable and self-serving, not to be trusted or admired.

Rumours of their secret vices were also rife.

King Philip IV of France who butchered the Knights Templar

An English chronicler by the name of John of Salisbury recorded his belief that 'when they convene in their lairs late at night, after speaking of virtue by day they shake their hips in nocturnal folly and exertion'.

Such thoughts became more and more commonplace, particularly after the Templars' core activities switched away from crusades in the Holy Land (where Muslim forces were increasingly in the ascendancy, entrenched and not easy to oust) to the exercise of wealth and power at home.

So it was little surprise that someone like Esquin would hear the rumours and sell them on.

When that out-and-out thug Philip IV of France swooped in his dawn raids, God's warriors caved in. Hundreds, many of them middle-aged men long past their warrior days, were placed under lock and key in dungeons.

To make them confess, they were tortured — starved, deprived of sleep, shackled, racked, burnt on the feet and hauled up in the strappado, a device that dislocated the shoulders by lifting the victim up by his wrists tied behind his back.

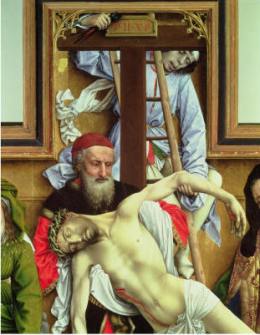

Most submitted to these horrors, including James of Molay, the order's Grand Master. From teenagers to wizened old men, from the highest-ranking officers to the meanest labourers, Templar brothers lined up before their black-clad interrogators and told their tormentors exactly what they wanted to hear.

They admitted denying Christ and spitting on the cross during 'the foul rigmarole' of their initiation ceremonies.

One senior knight confessed to allowing some in the order to relieve what he called 'the heat of nature' by carnal deeds with other knights.

All the accused seemed to be following the same script in their confessions, and any who deviated were racked until they got their story right.

As an added incentive, they were promised a pardon if they confessed their heresies and returned to the faith of the holy Church; otherwise they would be condemned to death.

No one stepped forward to offer them help or even speak on their behalf, despite their two centuries of heroic deeds.

The Pope tried to rein in the persecution, though he himself was under Philip's thumb. The best he was able to achieve was to acknowledge their confessions and offer them forgiveness and absolution.

In England, the unreliable King Edward II at first derided the accusations against the Templars as absurd but then, for his own political reasons, went along with the condemnations.

More and more 'confessions' were forthcoming.

By then, two-and-a-half years had elapsed since the original arrests and a handful of Templars, believing themselves wrongly accused and mistreated, determined to fight back, led by one Peter of Bologna.

He stood up and bravely told a papal commission that the allegations against them were 'obscene, false and mendacious' and had been proposed by 'liars and corruptors'. So-called confessions corroborating the accusations had been obtained by torture and threats of death.

Aware that his case against the Templars was in danger of collapsing, Philip acted like the tyrant he was.

There were 54 Templars currently on trial before an ecclesiastical court in the city of Sens, not far from Paris. Suddenly, he announced they were to be burnt at the stake without delay.

Despite frantic efforts by Peter of Bologna to launch a legal challenge, the royal will trampled over due process of law.

The Templars of Sens were strapped to wagons and taken to a field where dozens of stakes and pyres had been set up. Every one of them was burnt alive.

Peter of Bologna simply disappeared and was never seen again.

Faced with this brazen show of power and treachery, rank-and-file Templar resistance broke. Philip had won and the Templars were no more. Their property had been impounded, their wealth seized, their reputation shredded. Their members were imprisoned, tortured, killed, ejected from their homes and humiliated.

Those who survived this process either died in prison, were uprooted and sent to new homes, or in a few rare cases redeployed to new military orders.

The once-mighty order simply ceased to exist, its ruin precipitated by Esquin's 'kiss and tell' stories less than a decade earlier.

It was an astonishingly quick fall from extreme power and wealth to zero.

Yet the legend lived on.

The Templars still provide rich material for cranks, conspiracy theorists and fantasists. Their supposed secrets were at the heart of the blockbuster novel and film The Da Vinci Code.

The Norwegian fascist and terrorist Anders Breivik, who murdered 77 people in 2011, claimed to be part of a revived international Templar cell founded by nine men in London but with a growing worldwide membership of several dozen 'knights' and many more lay followers.

There is, says historian Dan Jones, a thriving industry in 'what-if' history about them, much of it resting on the false supposition that an order so wealthy and powerful could not simply have been rolled up and dissolved.

Alluring alternative histories have been concocted.

Did a small group of knights escape persecution in France with a stash of treasure? If so, did that include the Turin Shroud or the Ark of the Covenant?

Did the Templars set themselves up as a secret organisation elsewhere? Are they perhaps still out there, running the world from the shadows?

The answer to such questions is emphatically 'no' — but there is still no denying the seemingly timeless allure of God's warriors and their treasured place in our imaginations.

ok |

|

The Third Crusade

Part of the Crusades

To understand why the Knights Templar based themselves in the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem, the mysterious biblical figure of Joseph of Arimathea is worth knowing. He was, according to the Gospel of John, a secret disciple of Jesus – a rich Jewish merchant who may even have been the great uncle of Jesus.

Did Joseph of Arimathea possess relics sacred to the Knights Templar?

One blogger has noted that he would have to be the great uncle as being uncle would have meant he had the same name as Jesus’ father. Hardly likely two brothers would both be called Joseph. Another source stipulates that he was Mary’s uncle and so that problem is solved.

Joseph was an unusual choice for a disciple given that apparently, he was a Pharisee – the class of priest that gets a particularly bad write-up in the New Testament. You’ll perhaps remember that the Pharisees were deemed to be total hypocrites – moral on the outside, but corruption within.

It was Joseph who would provide a tomb for the body of the crucified messiah and also the shroud in which he was wrapped. The gospels claim he got permission from the Roman governor Pontius Pilate to take the body away. This begs the question how exactly he got in front of the governor to put forward this request and why it was accepted. Was he a very senior figure in local Jewish society? Did he bribe the governor?

Some have poured scorn on the idea of Jesus being removed so quickly noting that it was far more likely the Romans would have left the body of a trouble maker like Jesus to rot in public for a while on the cross and not allowed something as civilised as a tomb burial. But of course he had to be buried in order to be resurrected. And given that resurrection was supposed to be bodily – not just the soul – the idea of Christ’s body being pecked to bits by crows was never going to be very palatable.

More importantly for the Templars, Joseph was believed to be the man who collected some of Christ’s blood in a chalice as he hung on the crucifix. That chalice we know as the Holy Grail. It’s then claimed that Joseph travelled to England to spread the gospel. He arrived in Glastonbury – known as Avalon at that time – and baptised 18,000 people in one day at the nearby town of Wells. The Holy Grail was hidden away, maybe placed in a well that to this day is known at Glastonbury as the Chalice Well.

At this point I should also point out that it was widely believed in the Middle Ages that Joseph had brought Jesus as a youth to England before returning to the east. It’s even asserted that Jesus worked as a farm hand or a miner during his stay.

So with Joseph you have a lot of associations with important and sacred relics:

Were the Knights Templar established to protect these relics from being found or stolen? Or they were lost for centuries and the Templars were desperately looking for them under the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem? If they found these relics, did that account for the Templars’ sudden wealth and power? These and many more theories have circulated for centuries and at the centre of it all is a rather enigmatic figure of whom we really know very little: Joseph of Arimathea.

The Siege of Acre was the first major confrontation of the Third Crusade

Date 1189–1192

ResultTreaty of Ramla. Jerusalem remains under Muslim control. Crusader military victory. Italians consolidate control of Syrian ports. Muslims allow trade and unarmed Christian pilgrimages into the Holy Land.

Territorial

changes Cyprus, Acre, Jaffa, and much of the Levantine coast are annexed under Crusader control.

Belligerents

Crusader battles in the Levant (1096–1303). The Third Crusade (1189–1192), also known as the Kings' Crusade, was an attempt by European leaders to reconquer the Holy Land from Saladin (Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsuf ibn Ayyūb). It was largely successful, but fell short of its ultimate goal—the reconquest of Jerusalem.

After the failure of the Second Crusade, the Zengid dynasty controlled a unified Syria and engaged in a conflict with the Fatimid rulers of Egypt, which ultimately resulted in the unification of Egyptian and Syrian forces under the command of Saladin, who employed them to reduce the Christian states and to recapture Jerusalem in 1187. Spurred by religious zeal, Henry II of England and Philip II of France ended their conflict with each other to lead a new crusade (although Henry's death in 1189 put the English contingent under the command of Richard Lionheartinstead). The elderly Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa responded to the call to arms, and led a massive army across Anatolia, but drowned in a river in Asia Minor on June 10, 1190, before reachingthe Holy Land. His death caused the greatest grief among the German Crusaders. Most of his discouraged troops left to go home.

After driving the Muslims from Acre, Frederick's successor Leopold V of Austria and Philip left the Holy Land in August 1191. Saladin failed to defeat Richard in any military engagements, and Richard secured several more key coastal cities. Nevertheless, on September 2, 1192, Richard finalized a treaty with Saladin by which Jerusalem would remain under Muslim control, but which also allowed unarmed Christian pilgrims and merchants to visit the city. Richard departed the Holy Land on October 9. The successes of the Third Crusade would allow the Crusaders to maintain a considerable kingdom based in Cyprus and the Syrian coast. However, its failure to recapture Jerusalem would lead to the call for a Fourth Crusade six years later.

]Muslim unification

After the failure of the Second Crusade, Nur ad-Din Zangi had control of Damascus and a unified Syria.

Eager to expand his power, Nur ad-Din set his sights on the Fatimid dynasty of Egypt. In 1163, Nur ad-Din's most trusted general, Shirkuh set out on a military expedition to the Nile. Accompanying the general was his young nephew, Saladin.

With Shirkuh's troops camped outside of Cairo, Egypt's sultan, Shawar called on King Amalric I of Jerusalem for assistance. In response, Amalric sent an army into Egypt and attacked Shirkuh's troops at Bilbeis in 1164.

In an attempt to divert Crusader attention from Egypt, Nur ad-Din attacked Antioch, resulting in a massacre ofChristian soldiers and the capture of several Crusader leaders, including Bohemond III, Prince of Antioch. Nur ad-Din sent the scalps of the Christian defenders to Egypt for Shirkuh to proudly display at Bilbeis for Amalric's soldiers to see. This action prompted both Amalric and Shirkuh to lead their armies out of Egypt.

In 1167, Nur ad-Din once again sent Shirkuh to conquer the Fatimids in Egypt. Shawar also opted to once again call upon Amalric for the defence of his territory. The combined Egyptian-Christian forces pursued Shirkuh until he retreated to Alexandria.

Amalric then breached his alliance with Shawar by turning his forces on Egypt and besieging the city of Bilbeis. Shawar pleaded with his former enemy, Nur ad-Din to save him from Amalric's treachery. Lacking the resources to maintain a prolonged siege of Cairo against the combined forces of Nur ad-Din and Shawar, Amalric retreated. This new alliance gave Nur ad-Din rule over virtually all of Syria and Egypt.

Saladin's conquests

Shawar was executed for his alliances with the Christian forces, and Shirkuh succeeded him as vizier of Egypt. In 1169, Shirkuh died unexpectedly after only weeks of rule. Shirkuh's successor was his nephew, Salah ad-Din Yusuf, commonly known as Saladin. Nur ad-Din died in 1174, leaving the new empire to his 11-year old son, As-Salih. It was decided that the only man competent enough to uphold the jihad against the Franks was Saladin, who became sultan of both Egypt and Syria, and the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty.

Amalric also died in 1174, leaving Jerusalem to his 13-year old son, Baldwin IV. Although Baldwin suffered fromleprosy, he was an effective and active military commander, defeating Saladin at the battle of Montgisard in 1177, with support from Raynald of Châtillon, who had been released from prison in 1176. Later, he forged an agreement with Saladin to allow free trade between Muslim and Christian territories.

Raynald also raided caravans throughout the region. He expanded his piracy to the Red Sea by sending galleys not only to raid ships, but to assault the city of Mecca itself. These acts enraged the Muslim world, giving Raynald a reputation as the most hated man in the Middle East.

Baldwin IV died in 1185 and the kingdom was left to his nephew Baldwin V, whom he had crowned as co-king in 1183. Raymond III of Tripoli again served as regent. The following year, Baldwin V died before his ninth birthday, and his mother Princess Sybilla, sister of Baldwin IV, crowned herself queen and her husband, Guy of Lusignan, king.

It was at this time that Raynald, once again, raided a rich caravan and had its travelers thrown in prison. Saladin demanded that the prisoners and their cargo be released. The newly crowned King Guy appealed to Raynald to give in to Saladin's demands, but Raynald refused to follow the king's orders.

The Near East, c. 1190, at the outset of the Third Crusade.

[edit]Siege of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

It was this final act of outrage by Raynald which gave Saladin the opportunity he needed to take the offensive against the kingdom. He laid siege to the city of Tiberias in 1187. Raymond advised patience, but King Guy, acting on advice from Raynald, marched his army to the Horns of Hattin outside of Tiberias.

The Frankish army, thirsty and demoralized, was destroyed in the ensuing battle. King Guy and Raynald were brought to Saladin's tent, where Guy was offered a goblet of water because of his great thirst . Guy took a drink and then passed the goblet to Raynald. Saladin would not be forced to protect the treacherous Raynald by allowing him to drink, as it was custom that if you were offered a drink, your life was safe. When Raynald accepted the drink, Saladin told his interpreter, "say to the King: 'it is you who have given him to drink'". Afterwards, Saladin beheaded Raynald for past betrayals. Saladin honored tradition with King Guy; Guy was sent to Damascus and eventually ransomed to his people, one of the few captive crusaders to avoid execution.

By the end of the year, Saladin had taken Acre and Jerusalem. Pope Urban III is said to have collapsed and died upon hearing the news. However, at the time of his death, the news of the fall of Jerusalem could not yet have reached him, although he knew of the battle of Hattin and the fall of Acre.

Preparations

The new pope, Gregory VIII proclaimed that the capture of Jerusalem was punishment for the sins of Christians across Europe. The cry went up for a new crusade to the Holy Land. Henry II of England and Philip II of Franceended their war with each other, and both imposed a "Saladin tithe" on their citizens to finance the venture. In Britain, Baldwin of Exeter, the archbishop of Canterbury, made a tour through Wales, convincing 3,000 men-at-arms to take up the cross, recorded in the Itinerary of Giraldus Cambrensis.

"Death of Frederick of Germany" by Gustav Dore

Barbarossa's crusade

The elderly Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa responded to the call immediately. He took up the Cross atMainz Cathedral on March 27, 1188 and was the first to set out for the Holy Land in May 1189 with an army of about 100,000 men, including 20,000 knights. An army of 2,000 men from the Hungarian prince Géza, the younger brother of the king Béla III of Hungary also went with Barbarossa to the Holy Land.

The Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelus made a secret alliance with Saladin to impede Frederick's progress in exchange for his empire's safety. Meanwhile, the Sultanate of Rum promised Frederick safety through Anatolia, but after much raiding Frederick lost patience and on May 18, 1190, the German army sacked Iconium, the capital of theSultanate of Rüm. Nevertheless Frederick's horse slipped on June 10, 1190, while crossing the Saleph River throwing him against the rocks. He then drowned in the river. After this, much of his army returned to Germany, in anticipation of the upcoming Imperial election. His son Frederick of Swabia led the remaining 5,000 men to Antioch. There, the emperor's body was boiled to remove the flesh, which was interred in the Church of St. Peter; his bones were put in a bag to continue the crusade. In Antioch, however, the German army was further reduced by fever. Young Frederick had to ask the assistance of his kinsman Conrad of Montferrat to lead him safely to Acre, by way of Tyre, where his father's bones were buried.

Richard and Philip's departure

Philip II depicted arriving in Palestine

Henry II of England died on July 6, 1189 following a defeat by his son Richard I (Lionheart) and Philip II. Richard inherited the crown and immediately began raising funds for the crusade. In July 1190, Richard and Philip set out jointly from Marseille, France for Sicily. Philip II had hired a Genoese fleet to transport his army which consisted of 650 knights, 1,300 horses, and 1,300 squires to the Holy Land.

William II of Sicily had died the previous year, and was replaced by Tancred, who placed Joan of England—William's wife and Richard's sister—in prison. Richard captured the capital city of Messina on October 4, 1190 and Joan was released. Richard and Philip fell out over the issue of Richard's marriage, as Richard had decided to marryBerengaria of Navarre, breaking off his long-standing betrothal to Philip's half-sister Alys. Philip left Sicily directly for the Middle East on March 30, 1191, and arrived in Tyre in mid-May. He joined the siege of Acre on May 20. Richard did not set off from Sicily until April 10.

Shortly after setting sail from Sicily, Richard's armada of 100 ships (carrying 8,000 men) was struck by a violent storm. Several ships ran aground, including one holding Joan, his new fiancée Berengaria, and a large amount of treasure that had been amassed for the crusade. It was soon discovered that Isaac Dukas Comnenus of Cyprus had seized the treasure. The young women were unharmed. Richard entered Limassol on May 6, and met with Isaac, who agreed to return Richard's belongings and send 500 of his soldiers to the Holy Land. Once back at his fortress ofFamagusta, Isaac broke his oath of hospitality and began issuing orders for Richard to leave the island. Isaac's arrogance prompted Richard to conquer the island within days.

Siege of Acre

King Guy was released from prison by Saladin in 1189. He attempted to take command of the Christian forces atTyre, but Conrad of Montferrat held power there after his successful defense of the city from Muslim attacks. Guy turned his attention to the wealthy port of Acre. He amassed an army to besiege the city and received aid from Philip's newly arrived French army. However, it was still not enough to counter Saladin's force, which besieged the besiegers. In summer 1190, in one of the numerous outbreaks of disease in the camp, Queen Sibylla and her young daughters died. Guy, although only king by right of marriage, endeavored to retain his crown, although the rightful heir was Sibylla's half-sister Isabella. After a hastily arranged divorce from Humphrey IV of Toron, Isabella was married to Conrad of Montferrat, who claimed the kingship in her name.

During the winter of 1190–91, there were further outbreaks of dysentery and fever, which claimed the lives ofFrederick of Swabia, Patriarch Heraclius of Jerusalem, and Theobald V of Blois. When the sailing season began again in spring 1191, Leopold V of Austria arrived and took command of what remained of the imperial forces. Philip of France arrived with his troops from Sicily in May.

Richard arrived at Acre on June 8, 1191 and immediately began supervising the construction of siege weapons to assault the city. The city was captured on July 12.

Richard, Philip, and Leopold quarreled over the spoils of their victory. Richard cast down the German standard from the city, slighting Leopold. Also, in the struggle for the kingship of Jerusalem, Richard supported Guy, while Philip and Leopold supported Conrad, who was related to them both. It was decided that Guy would continue to rule, but that Conrad would receive the crown upon his death.

Frustrated with Richard (and in Philip's case, in poor health), Philip and Leopold took their armies and left the Holy Land in August. Philip left 10,000 French crusaders in the Holy Land and 5,000 silver marks to pay them.

Saladin tried to negotiate with Richard for the release of the captured Muslim soldier garrison, which included their women and children, but on August 20, Richard thought that Saladin had delayed too much, and had 2,700 of the Muslim prisoners decapitated in full view of Saladin's army, who tried unsuccessfully to rescue them. Saladin then responded by killing all of the Christian prisoners he had captured.

Battle of Arsuf

After the capture of Acre, Richard decided to march to the city of Jaffa, where he could launch the attack on Jerusalem but on September 7, 1191, at Arsuf, 30 miles (50 km) north of Jaffa, Saladin attacked Richard's army.

Saladin attempted to lure Richard's forces out to be easily picked off, but Richard maintained his formation until theHospitallers rushed in to take Saladin's right flank, while the Templars took the left. Richard then won the battle.

Regicide and negotiations

Saladin and Richard assured the rights and protection of pilgrim and caravan routes that allowed travel to distant lands.

Following his victory, Richard took Jaffa and established his new headquarters there. He offered to begin negotiations with Saladin, who sent his brother, Al-Adil to meet with Richard. Negotiations (which had included an attempt to marry Richard's sister Joan to Al-Adil) failed, and Richard marched to Ascalon. Richard's forces were halted nearly 12 times by the forces of Saladin commanded by Ayaz al-Tawil a powerful Mamluk leader, who died in combat.

Richard called on Conrad to join him on campaign, but he refused, citing Richard's alliance with King Guy. He too had been negotiating with Saladin, as a defense against any attempt by Richard to wrest Tyre from him for Guy. However, in April, Richard was forced to accept Conrad as king of Jerusalem after an election by the nobles of the kingdom. Guy had received no votes at all, but Richard sold him Cyprus as compensation. Before he could be crowned, Conrad was stabbed to death by two assassins in the streets of Tyre. Eight days later, Richard's nephewHenry II of Champagne married Queen Isabella, who was pregnant with Conrad's child. It was strongly suspected that the king's killers had acted on instructions from Richard.

In July 1192, Saladin's army suddenly attacked and captured Jaffa with thousands of men, but Saladin had lost control of his army because of their anger for the massacre at Acre. It was believed that Saladin even told the Crusaders to shield themselves in the Citadel until he had regained control of his army. Richard was intending to return to England when he heard the news that Saladin and his army had captured Jaffa. Richard and a small force of 2000 men went to Jaffa by sea in a surprise attack. In the subsequent Battle of Jaffa (1192), the Ayyubids, being unprepared for a naval attack were overwhelmed. Richard then retook Jaffa and freed the Crusader prisoners, who proceeded to join his force. However, Saladin's forces still had numerical superiority and counter-attacked. Saladin intended a stealth and surprise attack at dawn, but his forces were discovered. Saladin still attacked though, but his men were lightly armored and suffered very heavy casualties due to the Crusader archers. The battle to retake Jaffa ended in complete failure for Saladin who was forced to retreat. This battle greatly strengthened the position of the coastal Crusader states.

On September 2, 1192, following his defeat at Jaffa, Saladin was forced to finalized a treaty with Richard by whichJerusalem would remain under Muslim control, but which also allowed unarmed Christianpilgrims and traders to visit the city. Richard departed the Holy Land on October 9, 1192.

Aftermath

The Levant after the Third Crusade in 1200.

Neither side was entirely discontent nor satisfied with the results of the war. Though Richard had deprived the Muslims of important coastal territories as a result of his consistent victories over Saladin, many Christians in the Latin West felt disappointed that he had elected not to pursue Jerusalem. Likewise, many in the Islamic world felt disturbed that Saladin had failed to drive the Christians out of Syria and Palestine. Trade, however, flourished throughout the Middle East and in port cities along the Mediterranean coastline.

Saladin's servant and biographer Baha al-Din recounted Saladin's distress at the successes of the Crusaders:

'I fear to make peace, not knowing what may become of me. Our enemy will grow strong, now that they have retained these lands. They will come forth to recover the rest of their lands and you will see every one of them ensconced on his hill-top,' meaning in his castle, 'having announced, “I shall stay put” and the Muslims will be ruined.' These were his words and it came about as he said.

Richard was arrested and imprisoned in December 1192 by Duke Leopold, who suspected him of murdering his cousin Conrad of Montferrat, and had been offended by Richard casting down his standard from the walls of Acre. He was later transferred to the custody of Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor, and it took a ransom of one hundred and fifty thousand marks to obtain his release. Richard returned to England in 1194 and died of a crossbow bolt wound in 1199 at the age of 41.

In 1193, Saladin died of yellow fever. His heirs would quarrel over the succession and ultimately fragment his conquests.

Henry of Champagne was killed in an accidental fall in 1197. Queen Isabella then married for a fourth time, toAmalric of Lusignan, who had succeeded his brother Guy, positioned as King of Cyprus. After their deaths in 1205, her eldest daughter Maria of Montferrat (born after her father's murder) succeeded to the throne of Jerusalem.

Richard's decision not to attack Jerusalem would lead to the call for a Fourth Crusade six years after the third ended in 1192. However, Richard's victories facilitated the survival of a wealthy Crusader kingdom centered on Acre. Historian Thomas Madden summarizes the achievements of the Third Crusade:

...the Third Crusade was by almost any measure a highly successful expedition. Most of Saladin's victories in the wake of Hattin were wiped away. The Crusader kingdom was healed of its divisions, restored to its coastal cities, and secured in a peace with its greatest enemy. Although he had failed to reclaim Jerusalem, Richard had put the Christians of the Levant back on their feet again.

Accounts of events surrounding the Third Crusade were written by the anonymous authors of the Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi (a.k.a. the Itinerarium Regis Ricardi), the Old French Continuation of William of Tyre (parts of which are attributed to Ernoul), and by Ambroise, Roger of Howden, Ralph of Diceto, and Giraldus Cambrensis.

| " Lionheart"

Richard the Lionheart

King of England (more..) Reign 6 July 1189 – 6 April 1199 Coronation 3 September 1189 Predecessor Henry II Successor John Regent Eleanor of Aquitaine; William Longchamp (Third Crusade) Consort Berengaria of Navarre Issue Philip of Cognac House House of Plantagenet Father Henry II of England Mother Eleanor of Aquitaine Born 8 September 1157(1157-09-08) Beaumont Palace, Oxford Died 6 April 1199(1199-04-06) (aged 41) Châlus, Limousin Burial Fontevraud Abbey, France

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 6 July 1189 until his death. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Count of Nantes, and Overlord of Brittany at various times during the same period. He was known as Cœur de Lion, or Richard the Lionheart, even before his accession, because of his reputation as a great military leader and warrior.[1] The Saracens called him Melek-Ric or Malek al-Inkitar - King of England.[2]

By the age of sixteen Richard was commanding his own army, putting down rebellions in Poitou against his father, King Henry II.[1] Richard was a central Christian commander during the Third Crusade, effectively leading the campaign after the departure of Philip Augustus and scoring considerable victories against his Muslim counterpart, Saladin, but was unable to reconquer Jerusalem.[3]

Although speaking only French and spending very little time in England (he lived in his Duchy of Aquitaine in the southwest of France, preferring to use his kingdom as a source of revenue to support his armies),[4] he was seen as a pious hero by his subjects.[5] He remains one of the very few Kings of England remembered by his epithet, rather than regnal number, and is an enduring, iconic figure in England.

Tel Megiddo, entry gate

Known under its Greek name Armageddon.

Megiddo was a site of great importance in the ancient world, as it guarded the western branch of a narrow pass and an ancient trade route which connected the lands of Egypt and Assyria. Because of its strategic location at the crossroads of several major routes, Megiddo and its environs have witnessed several major battles throughout history. The site was inhabited from approximately 7000 BC to 586 BC (the same time as the destruction of the First Israelite Temple in Jerusalem by the Babylonians, and subsequent fall of Israelite rule and exile). One of its claims to importance is the fact that since this time it has remained uninhabited, thereby preserving the ruins of its time periods pre-dating 586 BC without newer settlements disturbing them.

Megiddo is mentioned in Ancient Egyptian writings because one of Egypt's mighty kings, Thutmose III, waged war upon the city in 1478 BC. The battle is described in detail in the hieroglyphics found on the walls of his temple in Upper Egypt. Named in the Bible Derekh HaYam (Hebrew: דרך הים), or "Way of the Sea," it became an important military artery of the Roman Empire and was known as the Via Maris.

In 2005, the remains of Megiddo were designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO as part of the Biblical Tels - Megiddo, Hazor, Beer Sheba.

Tel Megiddo, ruins on the citadell

Known under its Greek name Armageddon.

Megiddo was a site of great importance in the ancient world, as it guarded the western branch of a narrow pass and an ancient trade route which connected the lands of Egypt and Assyria. Because of its strategic location at the crossroads of several major routes, Megiddo and its environs have witnessed several major battles throughout history. The site was inhabited from approximately 7000 BC to 586 BC (the same time as the destruction of the First Israelite Temple in Jerusalem by the Babylonians, and subsequent fall of Israelite rule and exile). One of its claims to importance is the fact that since this time it has remained uninhabited, thereby preserving the ruins of its time periods pre-dating 586 BC without newer settlements disturbing them.

Megiddo is mentioned in Ancient Egyptian writings because one of Egypt's mighty kings, Thutmose III, waged war upon the city in 1478 BC. The battle is described in detail in the hieroglyphics found on the walls of his temple in Upper Egypt. Named in the Bible Derekh HaYam (Hebrew: דרך הים), or "Way of the Sea," it became an important military artery of the Roman Empire and was known as the Via Maris.

Tel Megiddo, Biblical site

Known under its Greek name Armageddon.

Megiddo was a site of great importance in the ancient world, as it guarded the western branch of a narrow pass and an ancient trade route which connected the lands of Egypt and Assyria. Because of its strategic location at the crossroads of several major routes, Megiddo and its environs have witnessed several major battles throughout history. The site was inhabited from approximately 7000 BC to 586 BC (the same time as the destruction of the First Israelite Temple in Jerusalem by the Babylonians, and subsequent fall of Israelite rule and exile). One of its claims to importance is the fact that since this time it has remained uninhabited, thereby preserving the ruins of its time periods pre-dating 586 BC without newer settlements disturbing them.

Megiddo is mentioned in Ancient Egyptian writings because one of Egypt's mighty kings, Thutmose III, waged war upon the city in 1478 BC. The battle is described in detail in the hieroglyphics found on the walls of his temple in Upper Egypt. Named in the Bible Derekh HaYam (Hebrew: דרך הים), or "Way of the Sea," it became an important military artery of the Roman Empire and was known as the Via Maris.

O Jerusalem : Mount Temple Explanada del Templo

Jerusalem, located in the Judean Mountains, between the Mediterranean Sea and the northern edge of the Dead Sea, is one of the oldest cities in the world and it is considered a holy city for three of the mayor monotheist religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. For such reason, in the course of its history, Jerusalem has been destroyed twice, besieged 23 times, attacked 52 times, and captured and recaptured 44 times. According to the majority opinion the name comes from the words “yeru” (house) and “shalom” (peace), i.e. “House of peace” (paradoxically).

It only has an area of 0.9 square kilometer (0.35 square mile), but the Old City has sites of key religious importance, such as the Temple Mount, the Western Wall, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque. Within the old city there are, 1204 synagogues, 158 churches, and 73 mosques. The old walled city, has been traditionally divided into four quarters, Armenian, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim. Actual walls were erected in 1538 by Suleiman and have 4,5 km, with 43 towers and 11 gates (only 7 opened). Jerusalem is the holiest city in Judaism and has been the spiritual center of the Jewish people since c. 1000 BCE, when David the King of Israel first established it as the capital of the Jewish Nation, and his son Solomon commissioned the building of the First Temple in the city, destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar, and then the site for the second temple, destroyed by Tito. The city is mentioned in the Bible 632 times. Today, the Western Wall, a remnant of the wall surrounding the Second Temple, is a Jewish holy site second only to the Holy of Holies on the Temple Christianity reveres Jerusalem for its significance in the life of Jesus. According to the New Testament, Jesus was brought to Jerusalem soon after his birth and later in his life cleansed the Second Temple. His mortal life finished at Golgotha, the site of the crucifixion. The land currently occupied by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (erected by Constantine I) is considered one of the top candidates for Golgotha and thus has been a Christian pilgrimage site for the past two thousand years. Jerusalem is considered the third-holiest city in Islam, primarily due to Muhammad's Night of Ascension (c. AD 620). Muslims believe Muhammad was miraculously transported one night from Mecca to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, whereupon he ascended to Heaven to meet previous prophets of Islam. Today, the Temple Mount is topped by two Islamic landmarks intended to commemorate the event—al-Aqsa Mosque (the fartherst … from Mecca), and the Dome of the Rock, from which Muslims believe Muhammad ascended to Heaven. In 1119, after the First Crusade, the French knight Hugues de Payens and his relative Godfrey de Saint-Omer, proposed the creation of a monastic order for the protection of pilgrims. King Baldwin II of Jerusalem agreed to their request, and gave them space for a headquarters on the Temple Mount, in the captured Al Aqsa Mosque, where it was believed to be the ruins of the Temple of Solomon. The Crusaders therefore referred to the Al Aqsa Mosque as Solomon's Temple, and it was from this location that the Order took the name of Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon, or "Templar" knights. The Order, with nine knights, remained nine years within the Temple premises. After that period of time, the Order started growing and getting rich. What did the find? The rest is part of the history. O Jerusalem Dome of the Rock La Cúpula de la Roca

Jerusalem, located in the Judean Mountains, between the Mediterranean Sea and the northern edge of the Dead Sea, is one of the oldest cities in the world and it is considered a holy city for three of the mayor monotheist religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. For such reason, in the course of its history, Jerusalem has been destroyed twice, besieged 23 times, attacked 52 times, and captured and recaptured 44 times. According to most opinions, the name comes from the words “yeru” (house) and “shalom” (peace), i.e. “House of peace” (paradoxically).

It only has an area of 0.9 square kilometer (0.35 square mile), but the Old City has sites of key religious importance, such as the Temple Mount, the Western Wall, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque. Within the old city there are, 1204 synagogues, 158 churches, and 73 mosques. The old walled city, has been traditionally divided into four quarters, Armenian, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim. Actual walls were erected in 1538 by Suleiman and have 4,5 km, with 43 towers and 11 gates (only 7 opened). Jerusalem is the holiest city in Judaism and has been the spiritual center of the Jewish people since c. 1000 BCE, when David the King of Israel first established it as the capital of the Jewish Nation, and his son Solomon commissioned the building of the First Temple in the city, destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar, and then the site for the second temple, destroyed by Titus. The city is mentioned in the Bible 632 times. Today, the Western Wall, a remnant of the wall surrounding the Second Temple, is a Jewish holy site second only to the Holy of Holies on the Temple Christianity reveres Jerusalem for its significance in the life of Jesus. According to the New Testament, Jesus was brought to Jerusalem soon after his birth and later in his life cleansed the Second Temple. His mortal life finished at Golgotha, the site of the crucifixion. The land currently occupied by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (erected by Constantine I) is considered one of the top candidates for Golgotha and thus has been a Christian pilgrimage site for the past two thousand years. Jerusalem is considered the third-holiest city in Islam, primarily due to Muhammad's Night of Ascension (c. AD 620). Muslims believe Muhammad was miraculously transported one night from Mecca to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, whereupon he ascended to Heaven to meet previous prophets of Islam. Today, the Temple Mount is topped by two Islamic landmarks intended to commemorate the event—al-Aqsa Mosque (the fartherst … from Mecca), and the Dome of the Rock, from which Muslims believe Muhammad ascended to Heaven. In 1119, after the First Crusade, the French knight Hugues de Payens and his relative Godfrey de Saint-Omer, proposed the creation of a monastic order for the protection of pilgrims. King Baldwin II of Jerusalem agreed to their request, and gave them space for a headquarters on the Temple Mount, in the captured Al Aqsa Mosque, where it was believed to be the ruins of the Temple of Solomon. The Crusaders therefore referred to the Al Aqsa Mosque as Solomon's Temple, and it was from this location that the Order took the name of Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon, or "Templar" knights. The Order, with nine knights, remained nine years within the Temple premises. After that period of time, the Order started growing and getting rich. What did the find? The rest is part of the history.

The heart of Richard I was buried in the Cathedral of Rouen, France, with mint, frankincense, mercury, creosote and daisies

Richard the Lionheart ended up with a heart full of daisies, mint and frankincense, a French study of his mummified heart has discovered.

The analysis also uncovered elements like creosote, mercury and perhaps lime in the heart, which has been in the western French city of Rouen since his death in 1199.

The study’s leader, Philippe Charlier, suggests the flowers and spices were to give the king the ‘odour of sanctity’.

The study came out less than a month after a team of British archeologists uncovered the long-lost remains of 15th-century King Richard III - a relative but not a direct descendant of Richard I - under a car park in Leicester.

Unlike that crude ending, Richard the Lionheart, leader of the Third Crusade, was ceremoniously laid to rest in three places.

His entrails were interred in the central French town of Chalus, where he died in a skirmish with a rebellious baron; his body reposes at the Fontevraud Abbey, beside his father Henry II and later his mother Eleanor of Aquitaine; and his heart, wrapped in linen, pickled for posterity and placed in a lead box, was sent on to the Cathedral of Rouen.

In 1838, the heart, already turned to powder, was rediscovered, transferred to a glass box and placed in Rouen’s Departmental Museum of Antiquities.

Charlier, a forensic medical examiner, and his 11-member team used the latest biomedical techniques to decipher the composition of The Lionheart’s heart.

Philippe Charlier, a forensic medical examiner, shows the remains of King Richard I's heart, which has undergone analysis more than 810 years after he died

RICHARD THE LIONHEART

Born on 8 September 1157 in Oxford, son of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, Richard I is one of the most popular kings in England history after leading the Third Christian Crusade against Muslims who had captured Jerusalem in the 12th century.

He failed to take the city because of inner-feuds between his Crusader allies, but scored numerous victories against Saladin, his Muslim counterpart.

Despite his reputation in England, Richard spent most of his time in his lands in France, and mainly conversed in French dialects.

Richard died after a crossbow bolt pierced his shoulder during a siege of the castle of Chalus-Chabrol in the Limousin region of France.

He claims it is the oldest embalmed heart ever studied and, belonging to a king, certainly the most prestigious.

The study was published in Scientific Reports, part of the Nature Publishing Group.

The aim of the study was to discover how hearts were embalmed in the 12th century, Charlier said. The presence of incense in the potpourri was the most striking because, Charlier said, it had not been found in previous embalmings, even in corpses dating from the Middle Ages.

Charlier speculates that the incense, among the gifts offered to the infant Jesus by the three kings and reportedly used on the outside of his body at death, was meant to give The Lionheart a direct line to God.

Richard I is one of the most popular kings in England history after leading the Third Christian Crusade against Muslims who had captured Jerusalem in the 12th century.

He failed to take the city because of inner-feuds between his Crusader allies, but scored numerous victories against Saladin, his Muslim counterpart.

Despite his reputation in England, Richard spent most of his time in his lands in France, and mainly conversed in French dialects.

Richard died after a crossbow bolt pierced his shoulder during a siege of the castle of Chalus-Chabrol in the Limousin region of France.

HOW TO PRESERVE A ROYAL HEART

Microscopic analysis showed pollen grains from daisy, myrtle and mint. lso found were pine, oak, poplar, plantain and bellflower, likely airborne contaminants. Poplar and bellflower were blooming at the time of death, the study says.

Molecular analysis turned up frankincense, the white matter in the powder.

There were large amounts of lead - said to be contamination from the box cradling the heart - and traces of copper and mercury, or quicksilver- commonly used at the time.

There is also a suggestion that lime may have been used as a disinfectant.

How bodies were preserved back then 'is a field of much speculation and, thus, such a study provides some decent evidence,' said Frank Ruhli, a professor at the University of Zurich's Center for Evolutionary Medicine.

However, he said in an email that the study has limited impact because of its focus on a single organ and on only one, if well-known, person

Philippe Charlier with the box which contained the heart, wrapped in linen, which was full of daisies, as well as myrtle, mint and frankincense.

This engraving by Huyot depicts the battle where King Richard I was killed by Bertrand de Gourdon at the siege of the castle of Chalus, France

Richard I's heart was wrapped in linen, pickled, and placed in a lead box for burial at the Cathedral of Rouen.

|

Tomb of Richard the Lion Heart. Tomb of Richard the Lion |

No comments:

Post a Comment